Reading Time: About 11 minutes

I.

In the winter of 1777, a fifteen-year-old Connecticut farm boy named Joseph Plumb Martin was camped with what remained of the Continental Army near Morristown, New Jersey. He hadn’t been paid in months. His shoes had disintegrated. He was surviving on what he later described as “half a day’s allowance of beef for a week.”

Martin would go on to serve the entire war—eight years—and write one of the only surviving enlisted-man memoirs of the Revolution. In his trademark style, Ken Burns uses Martin’s story to thread the needle in his new documentary, The American Revolution. What’s striking about Martin’s account is something more relatable to me than patriotism. It’s his complaining. He complains constantly. About the food, the pay, the officers, the mud, the lice, the boredom, the terror.

At one point, he writes about soldiers “ichoring,” a term he seems to invent to describe the pus leaking from their frostbitten feet. At another, he describes men so hungry they boiled their shoes and ate them.

Yet Martin never left the ragtag patriot militia. Through Valley Forge. Through Yorktown. Through years of misery in the service of George Washington and an army that most modern organizational consultants would diagnose as having a catastrophic retention crisis.

Why?

This is the question that Burns keeps circling back to across twelve hours of documentary. And it’s the question that kept nagging at me as I read the White House’s new National Security Strategy, released this week. It’s a document that inadvertently reveals how little we understand about the American brand and what Martin and his fellow soldiers actually believed they were fighting for.

II.

I’ve spent most of my career studying why some brands achieve cultural permanence while others—often with superior products and bigger budgets—fade into obscurity or suffer through a lifetime of punching below their weight.

The answer is structural. In Legendary Brands, I proposed something I called the brand mythology cycle, a self-reinforcing system in which beliefs anchor onto agents who embody those beliefs, agents create narrative that transmits the beliefs across time and space, and narrative accumulates into culture, creating a cyclical framework that makes a brand feel inevitable and part of something larger than its commercial objective. Once established, that culture influences and sometimes reshapes the original beliefs, creating a kind of symbolic hurricane that draws energy from its own motion.

Think about Apple. The belief (form matters as much as function, and innovation usually stems from those willing to resist conformity) was inextricably linked to Steve Jobs as its agent. Jobs generated the first narratives with the 1984 commercial to launch Macintosh, later came the “Think Different” campaign, and of course the iconic black turtleneck and jeans, all symbols of a brand that challenges the status quo. That narrative birthed a culture—a worldwide community of people who identify as “Apple people,” who believe that their choice of technology says something meaningful about who they are. And that culture continuously reinforces the original belief, even though Jobs has been dead for fourteen years and Apple is now one of the world’s largest companies. To be honest, you have to squint your eyes very hard to see the traces of the rebel in the Apple brand today, yet the mythology endures.

The brand mythology cycle explains why some brands survive disasters that would kill others. When Johnson & Johnson faced the Tylenol poisoning crisis in 1982, they pulled every bottle from every shelf at a cost of over $100 million because their mythology was built on trust, and their agents understood that violating that belief would collapse the entire system. When BP faced the Deepwater Horizon spill, they had no such mythology to draw upon other than an award-winning design system that was a facade for a belief system. Their culture couldn’t save them because “beyond petroleum” was nothing more than a tagline. It wasn’t in any way, shape or form the belief system that powered the company.

Nations work the same way. They’re just brands at a larger scale, operating on longer time horizons.

Which brings us back to Joseph Plumb Martin and his rotting shoes.

III.

The Continental Army had what we might call a mythology problem, but not in the way you might think.

The problem wasn’t that soldiers didn’t believe in the cause. The problem was that the belief and the experience were in constant tension. The mythology said they were fighting for liberty, for self-governance, for the radical proposition that ordinary people could determine their own fate. Everyone had read Common Sense by Thomas Paine, America’s first best-seller. The words and beliefs in that pamphlet stoked the flames of revolution so strongly that remnants of its prose found their way into the Declaration of Independence. Yet the revolutionaries’ lived experience was freezing, starving, and being ignored by the Continental Congress, which couldn’t agree on how to pay them.

Martin writes about this tension explicitly. He believed in the Revolution. He also thought about deserting constantly. The belief and the material reality existed in his mind simultaneously, uncomfortably, for eight years.

What Burns’s documentary makes clear (and what the historical record supports) is that the mythology won. Not because it erased the material complaints, but because it contained them. The soldiers understood their suffering as part of a larger story. The sacrifice was the point. You didn’t freeze at Valley Forge despite the cause; you froze because of the cause. The suffering was evidence of the belief’s seriousness.

This is how mythology cycles work. They metabolize contradiction.

IV.

Narrative is the strongest connective tissue in the brand mythology cycle. It is how the actions of agents for the belief system live in our heads. As I wrote in my book, Brand Real, experience is a narrative construct and it operates in two modes. One is like a surveillance camera, constantly recording but eventually looping and erasing because we can only retain so much information on the undulating folds of our brain. But the other is like a snapshot, and it gets embedded in our long-term memory. What causes the flash to fire and the print to be made is an emotionally charged burst—something good or bad, beautiful or monstrous, that transforms that moment in time to an enduring memory.

Imagine a nineteen-year-old kid from Iowa who has never left his home state, now storming a beach in France on June 6, 1944. He has no idea if he’ll survive the next thirty seconds. Bullets and shrapnel tear through the men on either side of him. He keeps moving forward. He does this not because France has offered fair trade terms. Not because Europe has agreed to pay its share of collective defense. Not because there’s a transactional benefit waiting on the other side. He does it because he genuinely believes that liberty is worth dying for–that tyranny anywhere is a threat to freedom everywhere. He believes that some things matter more than his own survival.

Now imagine a French farmer watching this happen–watching a boy from a country he’s never visited bleed out on his beach for his freedom.

What is the sequence of that experience? America sacrifices first, before asking for anything … before negotiations or burden-sharing debates. Instead of a demand, America has made a blood offering.

Memories like these, telegraphed virally around the world quite literally by photographer Robert Capa, created an emotional imprint that nourished the American myth for future generations. It’s why the French farmer’s grandchildren might still lay flowers at American graves in Normandy eighty years later. It’s why the Berlin wall was eventually destroyed by its own people and the Soviet Union eventually collapsed.

The American brand was built on a specific posture:

Belief → Sacrifice → Others witness → Attribution forms → Trust builds → Rewards follow.

The rewards that followed—trade dominance, alliance loyalty, global influence, the dollar as reserve currency—were outcomes of the equity in the mythology. They flowed to America because others wanted to be in relationship with a nation that stood for something and bled for it. More than that, we became role models.

V.

I was still thinking about Burns’s documentary when the White House released its National Security Strategy. The timing was coincidental. The contrast was not.

I’ve read it three times now, and what strikes me is what it assumes more than what it says. The document opens with a question: “What should the United States want?” The answer, developed across dozens of pages, is comprehensive:

- The world’s strongest economy

- The most lethal military

- The most advanced technology

- The most dominant financial system

- The most robust industrial base.

The word “power” appears thirty-two times. “Wealth” appears five times. “Prosperity” ten times.

The word “liberty” appears once and it’s used derisevly to criticize opposition to right-wing politics in Europe. There’s no articulation of liberty as an offering to the world, as a belief that might attract others, as the animating principle that explains why America exists in the first place.

The strategy treats American ideals as benefits—nice-to-have features that support the core value proposition of strength and wealth. But in the mythology cycle, beliefs are larger than benefits. They’re the engine. They’re what generates the agents, the narrative, the culture. They’re what makes the whole system cohere.

Worse, the strategy inverts the sequence that built American brand equity. We open to “what should the United States want?” not “what does America believe?” We lose the tension in the tapestry of our narrative. “What is America willing to sacrifice for?”

Want. Want. Want.

The language throughout reinforces this inversion. Allies are “free-riders” who must “pay their share.” Partners are evaluated by what they “contribute to our collective defense.” The strategy explicitly calls for “burden-shifting,” asking others to take primary responsibility for their regions.

This is demand before sacrifice and transactions over relationships. Ironically, we have seen this posture before. It was the same stance taken by the English Parliament under the reign of King George III; a posture that triggered American colonists so much that they vandalized ships in Boston Harbor and fanned the flames of revolution.

VI.

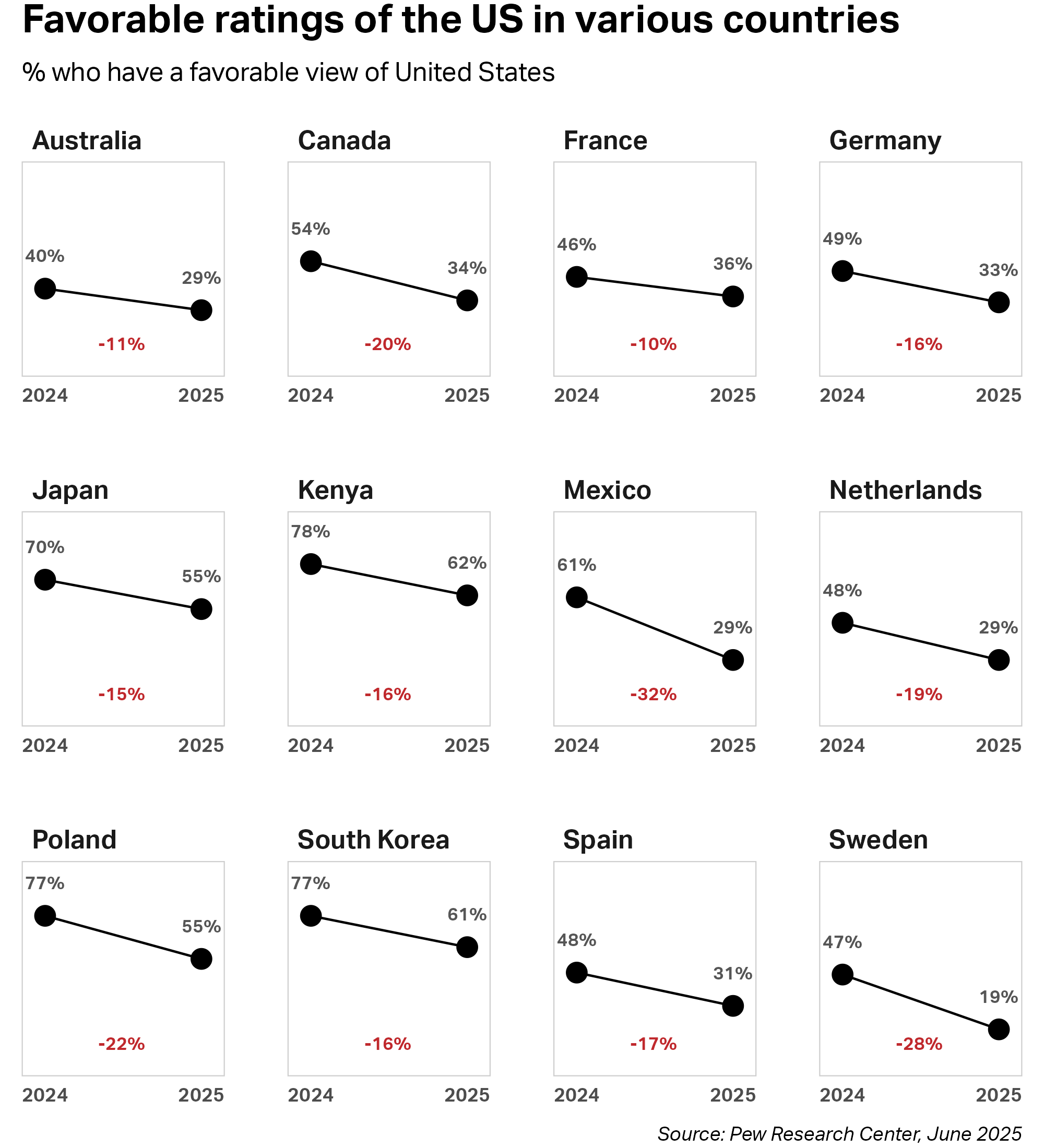

The data already shows the damage.

According to a June, 2025 study by the Pew Research Center, U.S. favorability has dropped significantly in fifteen countries since 2024. In Mexico, the decline was thirty-two points—from 61% favorable to 29%. In Canada, twenty points. In Sweden, twenty-eight points.

But here’s the detail that matters most. Pew also tracks favorability toward China. And for the first time in the survey’s history, the gap is closing. In Canada, both the United States and China now sit at 34% favorable. The U.S. dropped twenty points to get there. China rose thirteen.

When the narrative of America was rooted in the belief of liberty, we occupied rare competitive space that provided economic advantage. But if our story revolves around the value proposition that strength and wealth deliver transactional advantage, you’re playing on terrain where China can match you. They have strength. They have wealth. They’re very good at transactional relationships. Their Belt and Road Initiative has signed up 149 countries precisely because it offers economic benefit without ideological expectation.

China has its own brand mythology, but it isn’t something others want to join. Their story is national rejuvenation. It’s a compelling, populist narrative for Chinese citizens, but not one that translates to universal values. No one in Brazil or Indonesia lies awake dreaming of participating in China’s national rejuvenation.

For eighty years, America’s competitive advantage was simply that its foundational mythology invited others to make it their own. The “city on a hill.” The “leader of the free world.” The place where you could become something new. That mythology began a global revolution that liberated nations all around the world. That mythology attracted immigrants who built Silicon Valley. It attracted allies who funded NATO. It attracted dissidents who weakened the Soviet Union from within.

The 2025 strategy ignores this mythology. It considers only its consequences and reframes them as our foundational beliefs. We are due the spoils of a liberated world.

VII.

The Lowy Institute in Australia has been tracking global trade patterns for two decades. Their data tells the behavioral story beneath the attitudinal one.

In 2001, the year China joined the World Trade Organization, more than 80% of the world’s economies traded more with America than with China. By 2023, that had reversed. Seventy percent of the world now trades more with China. More than half trade twice as much with China as with the United States.

Map this geographically and it looks like a time-lapse of an empire receding. In 2001, American trade dominance stretched across Asia, South America, Africa, and Europe. By 2023, China had absorbed nearly all of it.

In October 2025, China overtook the United States as Germany’s largest trading partner. Germany. A NATO ally. A country that had been actively trying to reduce its dependence on China.

This is the brand manager’s nightmare. It’s a loyalty crisis that shows up in behavior before it shows up in surveys. By the time customers tell you they’ve lost faith, they’ve already switched.

VIII.

There’s a concept in brand mythology that I keep returning to. Mythologies are resilient. They survive scandals, recessions, and leadership changes. But they do have one fatal vulnerability. They cannot survive abandonment by their own agents.

When the people who are supposed to embody the belief stop believing it, the cycle breaks. Culture can no longer reinforce belief because there’s no belief left to reinforce. Yet there is something worse than abandonment: betrayal.

My colleague Deborah MacInnis, along with Martin Reimann, Valerie Folkes, and their collaborators, has spent years studying what happens when brands betray the customers who believed in them. Their research, published in the Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, reveals something that should alarm anyone thinking about America’s global position. The effects of betrayal are quite different from the effects of dissatisfaction. Betrayal is a categorically different psychological state.

When customers feel betrayed by a brand—when a brand they trusted fractures the relationship through what feels like a moral violation—they don’t just get angry at the brand. They get angry at themselves. They experience what MacInnis calls “self-castigation over one’s prior relationship with the brand.” They ruminate. They feel indignation. They want to get even.

The narrative of the American Revolution produced the greatest archetype of betrayal in a one-time hero named Benedict Arnold. The National Security Strategy summons his narcissistic spirit in its preamble, “in everything we do, we are putting America First.” That’s a far cry from “we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

Think about what "in everything we do, we are putting America first” means for the rest of the world.

When America signals that its own mythology was transactional all along—that the liberty talk was positioning, that the sacrifices were investments expecting return, that the “shining city on a hill” was really just a negotiating platform—the seeds of betrayal have been planted. These seeds grow into a specific psychological cascade. “We were fools to believe them.” “We trusted them and they played us.” “How could we have been so naive?”

The 2025 National Security Strategy reads like a document written by people who have stopped believing in the mythology they inherited. It’s indifferent to American ideals. It treats them as legacy code—still running somewhere in the background, occasionally useful for soft-power purposes, but not essential to the operating system. When they are mentioned at all in the strategy document they are tokens.

And this is how brands die: through slow incremental feelings of abandonment that leads those who believed to feel betrayed. The research is clear. Once customers feel betrayed, they rebel. They tell others. They oppose the brand because it stands against a belief system they adopted as their own. And that damage is very, very hard to undo.

IX.

Joseph Plumb Martin survived the war. He was discharged in 1783, returned to Connecticut, and lived another sixty-seven years—long enough to see the country he’d helped create expand to the Pacific, plant the seeds of a civil war over the contradiction at its heart, and begin the long process of becoming a global power.

In 1830, at the age of seventy, Martin published his memoir. It’s a funny, bitter, self-deprecating book. It’s nothing like the heroic narratives that had already begun to calcify around the Revolution. He complains about the pay. He complains about the food. He complains about the pension he never received.

But buried in the complaints is something else. He gives an account of why he stayed that elevated patriotism from the abstract to the tangible. His journey revolves around a strong belief that the thing he and his compatriots were building was worth the suffering. The sacrifice was the price of admission to a story larger than himself.

“I was there,” Martin writes at one point. “I was a participant in those events.”

A functioning mythology provides the sense that your participation matters. That you’re not just a customer or a subject or a taxpayer, but a participant in something that transcends the transaction.

The Greatest Generation didn’t storm Normandy for GDP growth. They didn’t freeze in Korea to optimize trade balances. They didn’t stare down Soviet missiles to maximize shareholder value.

They did it because they believed.

The world once wanted to be like us. That may be becoming less true as the relationship between our beliefs and our story has morphed into the art of the deal.