Reading Time: About 9 minutes

About a year ago, I was asked to meet with a serial CMO who wanted to collaborate on a study about the declining influence of marketing leaders. She had a few tours of duty under her belt, all at well-recognized enterprise technology companies. I expected to swap war stories. Instead, I was an audience to an indictment.

She lamented that marketing’s responsibilities were being delegated to sales or to newly installed Chief Revenue Officers. She noted shrinking sponsorship and advertising budgets. She complained about CFOs who demanded justification for every dollar as if she were running a lemonade stand instead of a global brand. Her seat at the strategic table, she said, had become a folding chair in the hallway.

I listened. I empathized. And then, somewhere between her third sigh and my second sip of coffee, I had an uncomfortable realization. The job wasn’t dying. You’re just doing it wrong.

I didn’t say this, of course. What I said was that I’d witnessed some of what she described, but I’d also seen something different. I’d seen more executives with marketing DNA moving into CEO, president, and GM roles. According to Spencer Stuart, the average tenure of a CMO has grown from around two years a decade ago to over four years today. I don’t think the CMO is an endangered species. But a certain kind of CMO might be.

Her frustration was real. She worked hard. She had systematically built her marketing organizations to quantify their work. But the quantification was the problem. She was measuring clicks, impressions, share of voice. She focused on how busy, not how valuable marketing was. And that’s the fundamental mistake that has relegated far too many CMOs to the kids’ table of the C-suite.

Last week, I wrote about how product management had become a Feature Factory that overemphasized the tyranny of urgency and marginalized the importance of customer insight. The conversation that followed was illuminating. So many marketers surfaced to applaud the truth-telling. But now I need to turn the table. In the spirit of Jon Stewart at The Daily Show … Marketers, meet me at camera two.

It’s time to stop being the company’s storyteller and start being its fortune teller. Be the one who can project future revenue because you know, better than anyone, why customers buy and how long they’ll stay. You want a seat at the table? Help set it.

I.

The Oracle of Delphi was, for nearly a thousand years, the most influential prophet in the Western world. Kings traveled for weeks to consult her. Generals postponed invasions to hear her speak. She sat in a chamber beneath the Temple of Apollo and delivered pronouncements that shaped the fate of empires.

But there’s a tiny thing about the Oracle that everyone conveniently forgets. Her prophecies were almost always incomprehensible.

When Croesus, the wealthy king of Lydia, asked whether he should attack the Persian Empire, the Oracle replied that if he did, a great empire would fall. Croesus was delighted. He attacked. A great empire fell. His own.

The Oracle wasn’t wrong. She was just impossible to understand.

This turns out to be a useful analog for thinking about the modern Chief Marketing Officer. CMOs sit atop vast repositories of customer insight. They commission the ethnographies, field the surveys, map the buying journeys. They are, in principle, the sensory apparatus of the entire organization. They are the function that should tell everyone else what customers want and what they’ll do next.

And yet, when they deliver their findings to the C-suite, something curious happens. The CFO’s eyes glaze over. The CEO nods politely and moves to the next agenda item. The prophecy is delivered, but no one can decode it.

The CMO has become the Oracle of the C-Suite; possessed of genuine insight, but incapable of expressing it in terms that anyone else can act on.

II.

In 1990, a Stanford graduate student named Elizabeth Newton conducted a simple experiment. She asked one group of participants to tap out the rhythm of well-known songs (“Happy Birthday,” “The Star-Spangled Banner”) on a table. She asked another group to listen and guess the song.

The tappers predicted that listeners would identify the song about 50 percent of the time. The actual success rate was 2.5 percent.

The problem was simple. The tappers could hear the melody in their heads as they tapped. The listeners heard only a series of disconnected beats. The tappers were convinced they were communicating clearly. They weren’t.

Newton called this “the curse of knowledge.” Once you know something, you can’t imagine not knowing it, which makes you a terrible judge of whether you’re being understood.

This is the curse that afflicts modern marketing. CMOs live and breathe customer data. They can see the melody—the buying journeys, the pain points, the relationship between clicks and sales. But when they present to the C-suite, all that comes through is tapping. Awareness. Click-through rates. Impressions. A series of disconnected beats that don’t add up to a song anyone else can recognize.

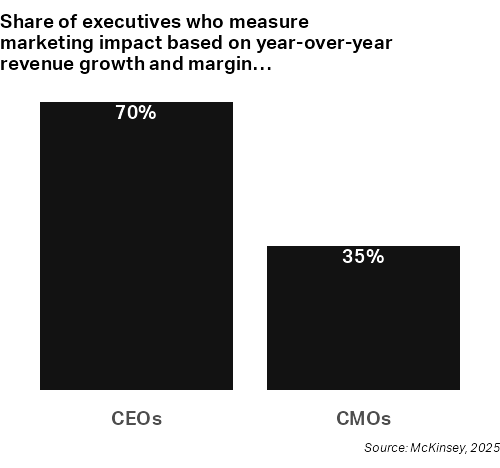

The data confirms the disconnect. McKinsey’s 2025 CMO Growth Research Survey found that 70 percent of CEOs measure marketing’s impact based on year-over-year revenue growth and margin. Only 35 percent of CMOs track those same metrics as a top priority.

Read that again.

The CEOs are measuring money. The CMOs are measuring something else entirely. It’s like showing up to a marriage counseling session and discovering your spouse thinks you’ve been arguing about how they stack the dishwasher when you’ve been arguing about whether you have a future together.

The Fall 2024 CMO Survey from Deloitte, the American Marketing Association, and Duke University, found that marketers allocate nearly 69 percent of their branding budgets to short-term performance, even though they say their ideal split would be 50/50 between short-term and long-term brand building. We know what we should be doing. We’re just not doing it.

I call this the Paradox of the Dashboard. The more we report, the more irrelevant we seem. We’ve built elaborate measurement systems that track everything except our contribution to the company’s financial future. The dashboard has become the corporate equivalent of a doctor who tracks your steps, calorie intake, and sleep quality, but never checks your weight or your pulse. “He had his best month yet,” they say. “We have no idea why he had a heart attack.”

III.

To be clear, there are many marketers who make the customer their primary focus. They’re doing the yeoman’s work, building the forecasts, earning their credibility. But too many senior marketers have drifted from that mission when it is badly needed. As one CFO told McKinsey’s researchers, “I need the CMO to tell me what customers want. They know them best, and I can’t make decisions without their input.”

That’s the job. Yes, media buying matters. Campaign management matters. But your real job is knowing the customer better than anyone else in the building.

It used to be said that any presidential candidate had better know—on a moment’s notice—how the Dow was trading and the current price of a gallon of milk. In marketing, CMOs better know the customer’s biggest pain point and why they need your company to heal it. And I mean know it! Not, “we did qual research in Q2.” Barf. Know! You should be able to say that “I’ve sat across from these people and watched them describe their frustration…” Know! The kind of knowing that doesn’t require a deck. The kind that survives a hard question from your CFO or a skeptical board member.

If your answer to “why do customers choose us?” starts with “well, our brand tracker shows…” you’ve already told everyone in the room that you don’t actually know.

When’s the last time you sat down with a customer and had a real conversation? A few years ago, I interviewed SoulCycle co-founder Julie Rice for a segment on this publication’s podcast. She revealed that when she and Elizabeth Cutler were co-CEOs, they spent more time in the company’s fitness studios than in corporate headquarters. “What I came to learn over the years,” she said, “is that when one person is brave enough to tell you something about the business, usually a lot more people think it and they just don’t have the guts to tell you.”

That’s deep customer knowledge possessed at the executive level that aligns decision-making across the enterprise, generates better customer experiences, and sustains a competitive advantage.

IV.

The path forward starts with a fundamental shift in what we measure. Michael Kaminsky framed it well in Harvard Business Review last September. CMOs are stuck in a trap that balances time between short-term performance goals and long-term brand building. To justify their effort, “marketing teams spend more energy proving past campaigns worked, rather than understanding what drives performance today.”

The CFO doesn’t care what you did yesterday. The CFO cares about how you can make tomorrow better.

The answer is Customer Lifetime Value. When I teach CLV to my graduate students I tell them that the beauty of CLV is that it is really a financial metric with marketing goodness baked in. It translates everything marketing knows about customers into a language the CFO already understands: future cash flows, discounted to present value. When you talk about CLV, you’re not asking finance to learn your language. You’re speaking theirs. You’re shifting the conversation from “here’s what we spent” to “here’s what we’ll earn.”

And the returns on getting this right are staggering. Frederick Reichheld’s research at Bain & Company demonstrated that increasing customer retention by just 5 percent can boost profits by 25 to 95 percent, depending on the industry. One of the foundational components of CLV is the margin multiplier, the ripple effect of retention. As the r (for retention) in the multiplier increases, the value of a customer multiplies. It’s a thing of beauty. McKinsey’s analysis shows that companies who excel at customer experience achieve more than double the revenue growth of their lagging peers. This occurs because great customer experiences correlate with higher retention. And those companies in the top quartile of retention outperform competitors by nearly 80 percent.

That’s the kind of “sweet-nothings” that will make your CFOs blush and lean forward instead of reaching for their phones to check the markets.

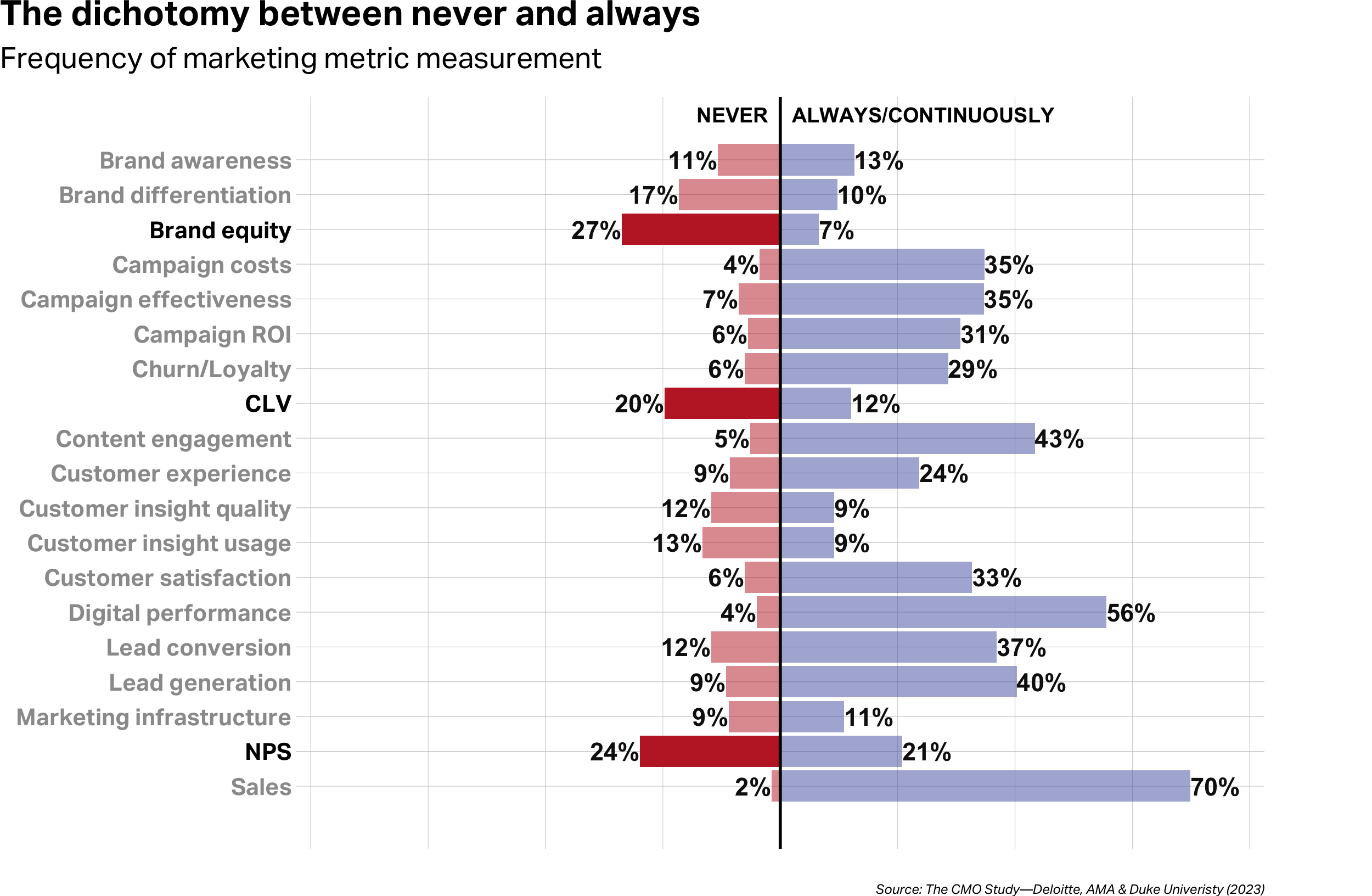

Sadly, according to The CMO Survey, one out of five CMOs say they never measure CLV. They join the 27% that also say they never measure brand equity, another basic metric that (when measured appropriately) helps marketing leaders improve margins and increase CLV.

V.

So what does it take to escape the Oracle’s curse? A few non-negotiables.

Adopt a new success metric. The CMO is only a success if they’re the first person others in the C-suite call when building next year’s revenue forecast or developing the strategic plan. Not the last to present. Not a box to check. The first call. If you’re not there yet, ask yourself what it would take to earn that spot. Can you forecast customer behavior with any degree of accuracy? Can you express this in a love language that is CFO-friendly?

Partner with the CFO to rebuild the measurement system. Mark-Hans Richer, CMO of Fortune Brands Innovations (and Harley-Davidson’s first ever CMO, who lasted more than 8 years in the job), puts it this way:

The relationship between the CMO and CFO is critical to the success of a business. I work on it. It’s not just one magic presentation that lays it all out. CMOs have to put forth the right data, work on the relationship, and build trust.

Stop defending your metrics. Start co-creating them with finance. Align all marketing activity with business outcomes investors care about. If you can’t tie your work to margin, earnings growth, or the lifetime value of your customers, you have work to do.

Become a coherent oracle. When marketing can demonstrate why customers buy, how long they’ll stay, and what they’ll be worth we create a competitive advantage that’s hard to replicate. McKinsey’s analysis of Fortune 500 executive teams found that companies with a single growth-focused executive like a CMO see up to 2.3 times more growth than those with fragmented customer ownership. Consolidate that authority. Own it. Be the undisputed customer whisperer.

Think like a general manager. Norm de Greve, CMO at General Motors, offers this advice:

People who spend their careers in marketing tend to know their areas very well, but when they become CMOs, the requirements for success fundamentally change. They change from being an expert in marketing to becoming a general manager who needs to speak the language of the CEO.

Your job isn’t to be the best marketer in the room. It’s to be the best business leader who happens to know more about customers than anyone else. CMOs should be the most natural candidate in the line of succession to the Chief Executive. Why? Because they know the customer. Without customers, there is no business.

VI.

The Oracle of Delphi eventually fell silent. The temple crumbled. The vapors stopped rising. Some historians believe she lost her power because geological conditions changed. Others think people simply stopped believing.

The CMO doesn’t have to share that fate. The customer insight is real. The data is there. The prophecy is true. It always was.

You just have to learn to deliver it in a language others can understand.

Stop speaking in riddles. Start projecting revenue. Own the customer.

The empire you save might be your own.