Reading Time: About 3 minutes

In his thought-provoking book The Storytelling Animal, Jonathan Gottschall constructs a compelling case that we are all natural born storytellers. We can’t help it. It is part of our brain’s wiring. It is how we comprehend the world. Even when we’re not trying, we’re always constructing stories.

I come back to this fact of life often, especially when someone says they can’t come up with a story; when they tell me they have writer’s block or they just aren’t creative enough to put a story together. That’s bunk. Each of us has been piecing stories together without much conscious thought since we were infants.

Gottschall provides a great example in his book when he discusses split-brain patients. A split-brain patient is someone whose corpus callosum stops functioning or is severed. The corpus callosum is a fibrous bundle of nerves that connects the left and right hemispheres of our brains. Neurosurgeons will sometimes split the corpus callosum in patients with severe, life-threatening seizure disorders. Sometimes, the corpus callosum is split as a result of tumor formation. Regardless of how it goes away, we have learned a lot about our storytelling instinct by studying people whose left and right brains stop communicating.

Our brain divides different functions between our two hemispheres. The left brain is specialized for tasks such as language and reasoning, while the right brain is more skilled at visual interpretation and focusing attention. When the two halves are connected, information that one half processes is shared with the other half so that we can do things like recognize a face (in the right brain) and then hypothesize about what kind of famous person they might be able to play in a movie (the left brain). But when the halves are split, that function is lost.

Gottschall describes a series of landmark experiments on split-brain subjects staged in the 1960’s to better understand this relationship between our two brains. For example, the right brain of a subject was exposed to a funny picture (accomplished by only allowing the left eye to view the picture because the left eye is wired to the right brain and vice versa). The subject would laugh. Then the researcher would ask the subject why they were laughing (a function of the left brain). Instead of saying “I don’t know” the subject would often make up a reason. Herein is proof of our storytelling instinct:>The left brain is a classic know-it-all; when it doesn’t know the answer to a question, it can’t bear to admit it. The left brain is a relentless explainer, and it would rather fabricate a story than leave something unexplained. Even in split-brain subjects, who are working with one-half of their brains tied behind their backs, these fabrications are so cunning that they are hard to detect except under laboratory conditions.

Tease the right brain and let the left brain run amok

A story (in the classical sense) is usually about a character in action. In fiction writing we often refer to the protagonist—the central character whose actions and activities propel the story forward. Think Hamlet and Indiana Jones and Erin Brockovich. In each instance, the story we have in our mind was successful because there was a clearly defined central character who overcomes giant obstacles to do something significant.

But sometimes we don’t have ideal storytelling situations. We don’t have a great protagonist, or maybe there are multiple protagonists. Maybe we have a great protagonist but we don’t have a very clear storyline. Does that mean we must move on to another project? Certainly not. In fact, you can stage a story by delivering the elements you have in a specific way that puts those different hemispheres of our brain to work. You can tantalize the right hemisphere and let the left hemisphere explain it. This is actually a powerful, and often more engaging approach to storytelling.

In a recent piece on his excellent podcast, How Sound, Rob Rosenthal described advice he often gives to radio producers who want to tell stories that don’t have strong characters in action. His advice builds off of tips from Mark Kramer’s book Telling True Stories, which is a useful storytelling primer for nonfiction writers and journalists. Rosenthal suggests 5 tips to compensate for a weak or nonexistent narrative:

Sharp images —which means make the story visual. Use the writing and interview tape and sound to create pictures for listeners

Strong characterization —allow listeners to really get to know someone and what makes them tick

Anecdotes —short stories within the larger story

Unique location —some place that’s maybe strange or hard to get to or surprising, that can help overcome a deficit in narrative

Clever production —it needs to be well done and artful. If it’s plain, it may not work.

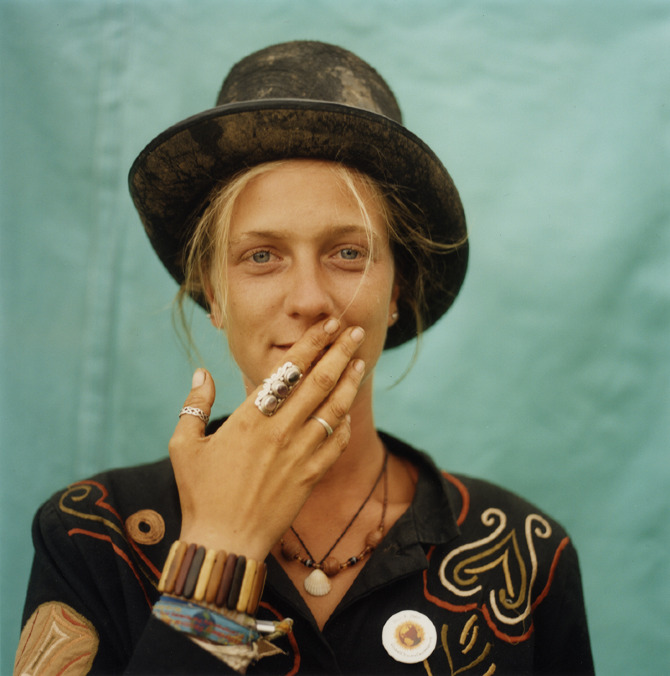

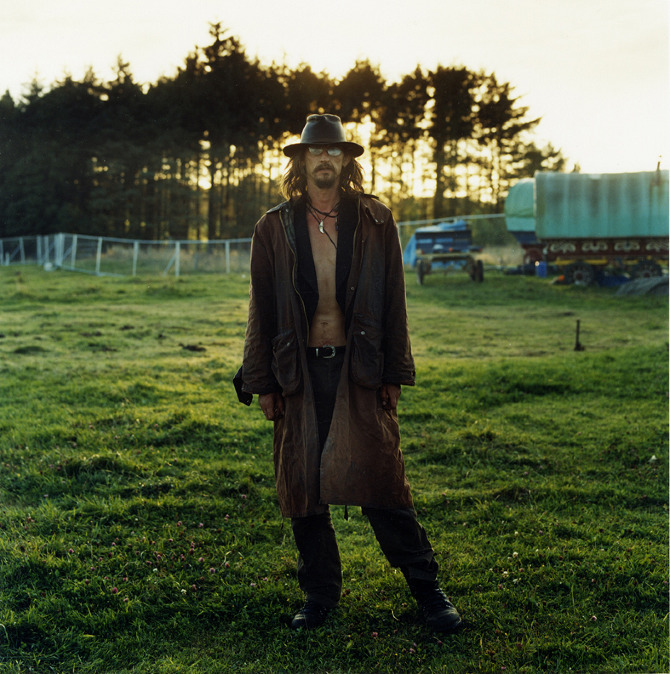

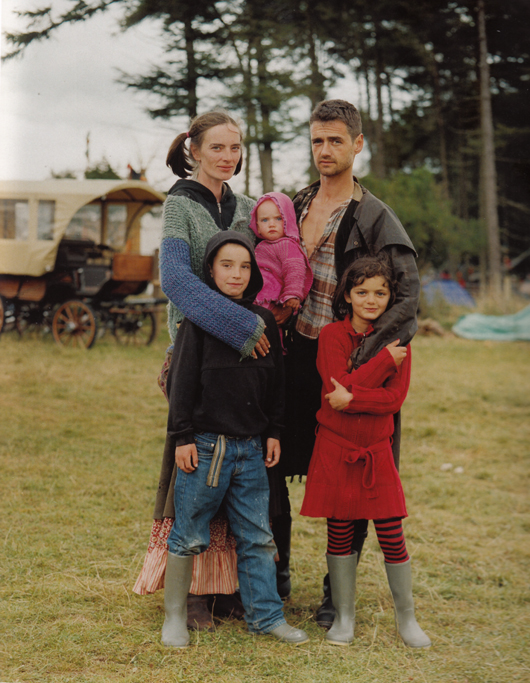

The new gypsies

All of these storytelling tips can be found in work I discovered this week by photographer Iain McKell. His book and exhibition The New Gypsies features a series of romantic images of modern day nomads—people who have chosen to live a gypsy life for over 10 years, roaming from place to place in the UK. Looking at the images, you don’t need any text or voiceover. They instantly captivate our visual mind with sharp images, strong characterization, visual anecdotes, remote locations, and a clever production aesthetic, all of which allows our reasoning mind to shape a powerful narrative.

The New Gypsies by Iain McKell